Commonwealth Games Stats Wrap: How Australia and India led the way

Unstoppable Mooney, Australia’s death and middle overs dominance, Mandhana-Verma pyrotechnics and more statistical trends from the Commonwealth Games

The T20 World Cup, the 50-over World Cup, and now a Gold Medal at the Commonwealth Games.

Can someone run down to Ikea? Australia needs a new trophy cabinet.

Let’s take a look at the statistics behind Australia’s triumph in Birmingham and India’s Silver Medal finish.

Australia

Over the last five years, Alyssa Healy and Meg Lanning have been two of the best batters in the world across formats. However, for their standards, they both had poor tournaments with Healy aggregating a mere 48 runs and Lanning a mere 91 in five innings each.

Unsurprisingly, this resulted in Australia only managing to score at 6.27 runs per over in the powerplay, which was comfortably the worst among all four of the semi-finalists. They also lost wickets more frequently than any of the other three semi finalists, losing ten in total across the competition.

So, given these numbers, how did Australia manage to secure a gold medal?

A lot of credit goes to Beth Mooney who topped the tournament run charts with 179 runs at a strike rate of 133.6 in her 5 innings. Earlier this year, in a wrap up of Australia’s dominant batting at the 50-over World Cup, I highlighted how Mooney had the best non-boundary strike rate (NBSR) in that tournament, striking at 67.35 off non-boundary balls.

Well, guess what? She’s done it again in the T20 format!

She had the best NBSR out of all batters with at least 75 runs during the Commonwealth Games, striking at 76.6 off non-boundary balls. England’s Amy Jones was next at 70. We’ve said it before on All Over Cricket and we’ll say it again: Beth Mooney is the world’s best strike rotator. It’s near impossible to keep her quiet even when she isn’t getting boundaries away.

Yet, Mooney was not the only Australian batter to make game-defining (or tournament-defining) contributions. Tahlia McGrath, Ash Gardner, and Grace Harris stepped up at different points in Birmingham.

On two separate occasions against Pakistan and New Zealand, McGrath combined with Mooney to rescue Australia from early trouble in the powerplay. Throughout her time in Birmingham, McGrath averaged a brutal 4.3 balls per boundary, while scoring at a strike rate of 69.7 off non-boundary balls.

Among the top 20 tournament run-scorers, her overall strike rate of 148.8 was second only to Smriti Mandhana’s 151.4. McGrath and Mooney were the most consistent and most merciless duo in the middle overs. Moreover, Ash Gardner’s innings against India was a masterclass in taking a game deep. You couldn’t stop this trio from scoring boundaries or rotating the strike at will when boundaries were hard to come by.

When you plot NBSR against Balls per boundary, these three names occupy the top left quadrant of the scatter plot. They struck the best balance between strike rotation and boundary-hitting and made up for the inconsistencies of Lanning and Healy.

Overall, Australia scored at 8.67 in the middle overs (Overs 7-15), marginally behind South Africa’s 8.75 before pummelling 9.84 runs per over in the final five overs, which was ahead of second-placed India’s 9.23 runs per over.

If you’re not Australian, brace yourself. A look at their bowling statistics will make for a bumpy ride. It is hard to argue that Australia wasn’t the best bowling team in the competition. They conceded 5.9 runs per over in the powerplay, 6.42 in the middle, and just 6.69 at the death.

In spite of underwhelming with the bat in the first six overs, their bowlers ensured a powerplay run rate differential of 0.37. Their middle overs differential of 2.25 was also the best among all the semi-finalists.

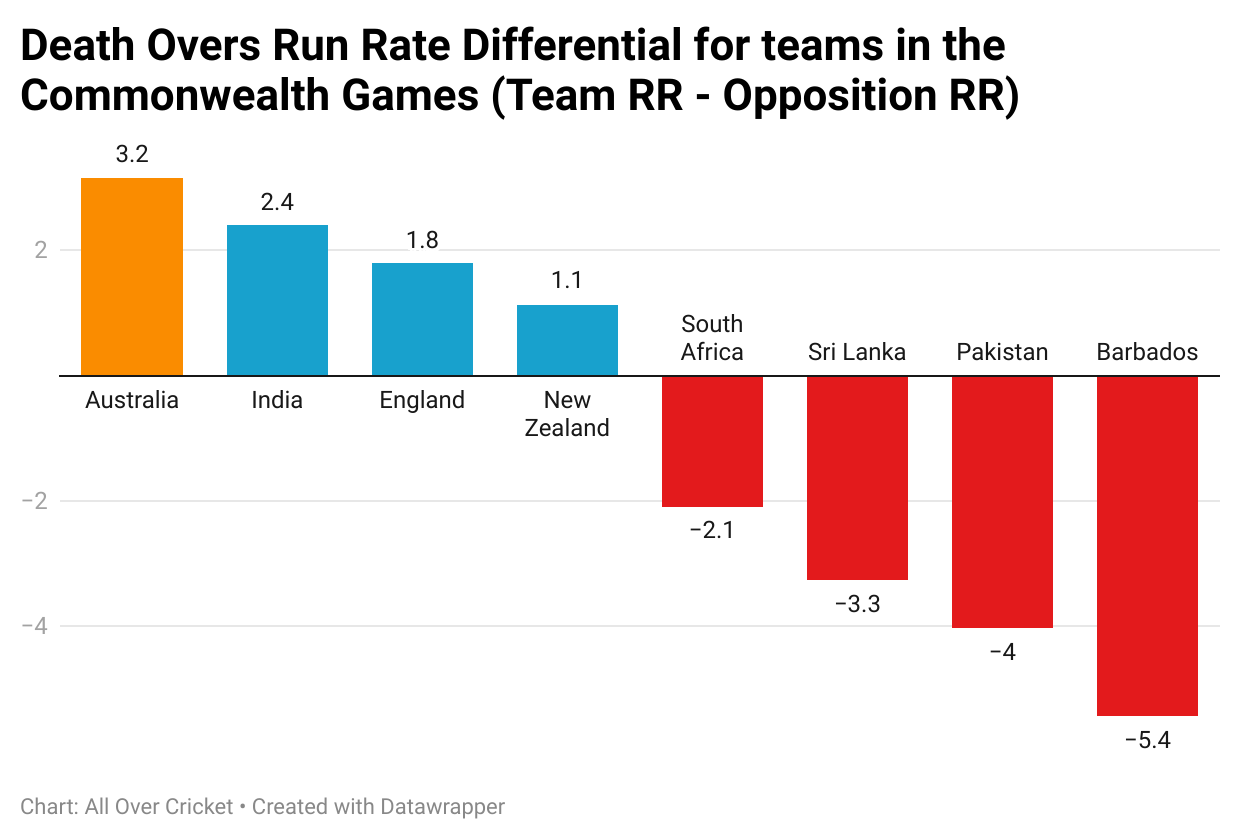

Their death overs differential, however, was simply scary. For every over of death overs batting, they scored an average of 3.15 runs more than their opponents.

To put it simply, Australia won Gold at the Commonwealth Games because they batted deeper than any other team, they were the best bowling team, they executed their skills at the death in all departments, and they held their nerve when it mattered most.

India

Smriti Mandhana and Shafali Verma were easily the most explosive opening pair in Birmingham. They’re a big reason why India’s batters had the best powerplay run rate among all teams, going at 8.38 runs per over when the field was up. Throughout the competition, Mandhana scored at a strike rate of 151.4, whereas Shafali struck at 144.6. Out of all batters with at least 75 runs, they had the best and third best strike rates, respectively.

Remarkably, India scored at or above 10 runs per over in three out of five powerplays. New Zealand was the only team to manage this even once.

How Mandhana and Shafali went about this makes for fascinating reading. Of all batters with at least 75 runs in the tournament, Mandhana and Shafali’s had the best balls per boundary ratio at 3.62 and 3.83, respectively.

However, on the same list of batters, Mandhana (40.8) and Shafali (48.5) also had the second and third worst non-boundary strike rates. There was no designated role of anchor or aggressor between these two. They both went for boundaries and didn’t care for singles. Their boom or bust approach paid rich dividends and was a cornerstone for India’s Silver-medal campaign.

As the opposition, if you were lucky enough to survive the onslaught from India’s two swashbucklers, you had your hands full with Jemimah Rodrigues and Harmanpreet Kaur. Rodrigues maintained an NBSR of 67.29 throughout India’s campaign, playing key innings against Barbados and England to prove that she should always bat in her favourite number three position, which has brought her so much success over the years in T20 leagues.

Harmanpreet, meanwhile, excelled at number four, which is arguably the toughest position to bat in T20 cricket. Sometimes, a number four batter will walk into bat during the powerplay. They have to rebuild, so they can’t take full advantage of the field being up. In other instances, they come in when the field is spread out, so it’s theoretically harder to score boundaries.

Yet, Harmanpreet Kaur has been in fabulous form ever since last year’s WBBL, where she won the player-of-the-tournament award. Since the end of the 2020 T20 World Cup, no batter has scored more runs at number four than Harmanpreet Kaur. Coming at two down, she has amassed 319 runs, striking at 126.58. Crucially, both of her two half-centuries in Birmingham came against the mighty Australians.

India’s returns with the ball also got better as the tournament progressed. It was baffling that they ever thought it was a good idea to drop Sneh Rana, one of their best all-format players over the last 12 months. Pooja Vastrakar’s return to the XI after recovering from Covid-19 also breathed life into India’s bowling attack.

The difference between India’s run rate in the powerplay and that of their opponents was 1.9. This was the highest powerplay run rate differential for any team. Renuka Singh Thakur, of course, had a huge role to play in this regard. Her iconic 4-fer against Australia on the opening day was arguably the best spell of the tournament.

In Vastrakar and Renuka, India have two reliable seamers, from whom the best may be yet to come. Deepti Sharma is perhaps India’s most-versatile all-phase bowler while Sneh Rana’s last over against England with just three fielders in the ring was a major contribution in a high-pressure situation. These four are the core around which India should be building their bowling attack.

A special mention goes to India’s fielding, which was just as good as Australia’s in the final. It was also one of the factors that allowed them to edge ahead of England in the semi-final.

Aside from a collapse that saw them lose 34 for 8 in 5.1 overs against Australia in the final, India had a top-quality campaign. In any other era gone by, their showing at the Commonwealth Games would have seen them run away with gold.

Yet, the concern for them and other teams in the world is that Australia just keep getting stronger.

And no, I haven’t forgotten about the elephant in the room! It comes up every time I pen a piece about India.

Given that the professionalization of the women’s game in Australia has outpaced other nations and because of the WBBL, Australia’s players are simply more battle-hardened than their Indian counterparts.

There is no gulf in talent between the two cricketing nations. Instead, in the absence of a Women’s IPL, India’s players simply don’t have the opportunity to test their mettle in nearly as many high-pressure, competitive situations.

Yes, India crumbled under pressure in the final. This, however, was largely a symptom of administrative failings from the richest board in world cricket.

Like what you read? Subscribe to All Over Cricket for more stories on women’s cricket and associate cricket!

You can also follow us on Twitter, where we often live tweet during big games and tournaments!